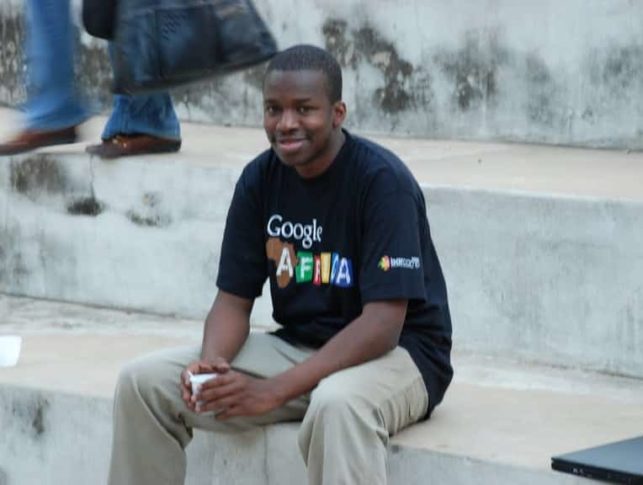

In 2009, Google opened an office in Dakar, the capital of West-African Francophone country Senegal. By 2015, much of West Africa is on the Internet thanks to an increase in infrastructure development, particularly with cell phones, and the work of one man: Tidjane Deme. Deme is a 40-year-old Senegalese Internet technician educated in France, and man who has played a huge part in the Africa’s Internet explosion.

Internet…in Africa?

To people living in the western world, the word “Africa” brings with it images of lions, elephants, subsistence living and poverty. It does not connote images of cosmopolitan teenagers, of families shopping for the latest cell phone cases or young people downloading music on their phones—yet these images are a much greater part of Senegalese society than images of wild animals. It was in 2008 that Google executives recognized Senegal’s commercial potential and first met with Tidjane Deme. The executives recruited Deme to coordinate their interests in French-speaking Africa (many coastal West African countries) because he could offer insights that would not be available to a western ex-patriate. His high-level of specialized education coupled with a life spent primarily in Dakar, Deme emerged as Google’s best man. Google was not able to woo Deme in 2008, but it took less than a year to appoint him head of the newly opened office in Dakar. Unlike neighboring Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire, Senegal did not have an existing 3G framework in 2009. Today, that has changed entirely: more Senegalese connect to the Internet through their phones (or wirelessly) than they do through fixed Internet outlets like computers.

Promoting Relevance

As access has increased so too has the need for relevant Internet media. Most westerners are unlikely to notice how western-centric the Internet is—that is precisely because they find the information readily available on Google or major news outlets to be relevant. For Sub-Saharan African Internet users, this is not the case. In a region where literacy rates remain low (according to the World Bank, about 66% of Senegalese between 15-24 are literate) video content is of the utmost importance in disseminating news. However, much of the available media represents only the western aspects of life: Senegalese news programs do not have the same type of budget or capacity as programs like CNN, while Senegalese pop-stars like Amadou & Miriam do not have millions of dollars to spend on music videos in the same way that Taylor Swift has. In order to increase the amount of Internet users (paying customers) Internet companies will need to up their game in terms of infrastructure—2G and 3G networks don’t cut it when millions of people are trying to access YouTube at the same time. Increasing Internet penetration promotes universal access by encouraging companies to increase their capacity, thus enabling more people to reap the benefits of open Internet.

Is Knowledge Worth More than Water?

When asked whether promoting paid-for Internet usage and openness to a country where 25% of the population does not have access to drinking water or and 50% lack access to basic health facilities was unethical, Deme pointed out that “we should definitely not be telling people you’re too poor to get the benefits of Internet. I think that would be ethically wrong.” (http://audio.californiareport.org/archive/R201405091630/d The California Report). Deme has a point. The amount of money that an individual user will spend on data for her/his cell phone to access the Internet would be but a drop in the proverbial bucket towards clean drinking water. This access, however, will enable individual users to learn more about the promises their government makes, and create a network of young people who can hold their government accountable through recorded speeches and media appearances.

To Infinity, and Beyond!

What started out with one intelligent, passionate and entrepreneurial Dakar-native has grown into Internet access for more than 20% of the population in less than a decade. Creating the demand and supply for high-tech services in a country where the majority of roads are not paved was no small feat. Deme has enabled almost one million Senegalese to tap into the infinite knowledge available on the Internet—promoting access has changed the way Senegalese, especially young people, relate to the world around them. Deme is yet another example of why the west’s view of Africa must change: western countries need to see countries like Senegal as peers and viable business options. If the investment by local government and foreign companies is made, the positive impact of open access to knowledge can only increase.