Angola is the latest nation to seek an aid package from the International Monetary Fund as its oil-dominated economy falters.

As its economy buckles under the weight of falling oil prices, Angola is turning to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout.

By one estimate, the West African nation faces a shortfall of $8 billion, or 9 percent of its gross domestic product, this year. Angola last borrowed from the IMF in 2009.

Angola is one of several cash-strapped African countries that are turning to the IMF for financial help as prices drop for commodities such as oil and minerals.

Ghana agreed to an aid package in 2015, it’s first from the IMF in six years. Zambia is also in talks for IMF aid, which would be its first since 2008. Zimbabwe has also asked the IMF for its first loan in nearly two decades.

Meanwhile, the IMF stopped a $55 million loan to Mozambique – part of a bailout approved last year – after discovering the country had failed to report $1 billion in unreported loans it owes.

South Africa and Nigeria may also be forced to turn to the IMF as their economies struggle.

Angola faces shortfall

Angola’s request was an about-face after the nation repeatedly said it would not turn to the IMF for help in the current crisis because the aid would come with too many conditions.

But the country’s reserves have fallen as oil prices stayed below $45 a barrel and the government is reluctant to cut services in advance of elections in 2017.

Oil accounts for 95 percent of Angola’s exports and about half of the government’s revenue. In addition to slumping oil revenues, the country has suffered a retrenchment by China, which has its own economic problems.

Monetary agency requires transparency

In exchange for IMF aid, the Angolan government is likely to be forced to be more transparent about its financial dealings as the international agency typically scrutinizes the finances of countries it assists.

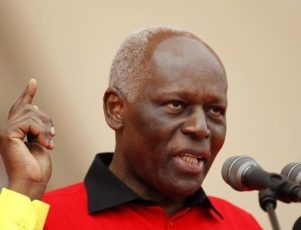

One criticism of Angola’s economy is the extent to which it is controlled by President José Eduardo dos Santos, who has ruled the country for more than three decades. While nearly half of the country’s population subsists on just over $1 per day, dos Santos’ daughter, Isabel dos Santos, is the richest woman in Africa, raising questions about the source of her wealth. Isabel dos Santos has denied using state money to enrich herself.

“The IMF stands ready to help Angola address the economic challenges it is currently facing by supporting a comprehensive policy package to accelerate the diversification of the economy, while safeguarding macroeconomic and financial stability,” Min Zhu, IMF deputy managing director, said in a statement.

One expert urged caution. Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, an Angola expert at Oxford University, noted that a study in 2011 by IMF staff found that the government could not account for $32 billion between 2007 and 2010.

“The IMF should use the leverage it has to extract serious concessions and tangible reforms from the government,” de Oliveira said.

Ghana receives bailout

Angola is the not the only country turning the IMF.

Ghana, an oil and gold producer, received a three-year, $918 million bailout in 2015. The country saw the value of its crude exports cut in half between 2014 and 2015, falling to $1.5 million in the first three quarters of last year as both prices and demand fell. Gold exports fell by nearly one third to $2.4 million.

In December, the IMF also agreed to a $283 bailout loan package for Mozambique that required the southern African nation to disclose all of its borrowing. In April, the IMF said it stopped a disbursement of $55 million after learning the country had not reported millions in loans by Credit Suisse Group and the Russian VTB Group.

Mozambique, a natural gas producer, saw exports fall by 14 percent in 2015.

Zambia, Africa’s second largest copper producer, saw a shortfall of 8 percent of gross domestic product in 2015 and is also seeking IMF assistance in 2016. Zimbabwe also expects an IMF loan in the third quarter of this year.

In addition to the IMF aid, the World Bank said it expects to lend up to $25 billion this year to countries reeling from falling commodity prices.

Read more