Kenya’s mango exports have jumped by 400 percent in the past five years, thanks in large part to a switch from chemical to bio pesticides to control fruit flies.

In the past, the troublesome insects forced mango farmers to leave a significant share of their crop on the ground or to use chemical pesticides that meant the fruit was not acceptable in many foreign import markets.

But the introduction of new methods of controlling pests using naturally occurring substances is giving mango farmers a boost.

Louis Matheka, sales manager for the exporter Mangos from Kenya, said mango production increased by 27 percent during the season that ended in April compared to a year earlier. At the same time, exports were up 30 percent. In the latest season, Kenya exported 26,000 metric tons of mangos, mostly to the Middle East.

Fruit fly spoils crops

Most of Kenya’s growers are small farmers who have struggled to make their mango crops pay because fruit fly infestations often resulted in more than half the fruit being wasted.

Erratic yields in turn made it difficult to enter and meet the requirements of formal contracts with exporters.

Meanwhile, fears of spreading fruit flies to importing countries along with high use of chemical pesticides meant the harvests were off-limits to many foreign import markets. Instead, farmers sold their fruit for lower prices at local markets.

But in recent years, companies have developed promising bio pesticide alternatives to help an estimated 60,000 Kenyan growers control fruit flies.

Project pioneers bio pesticide

One Kenyan company, Real IPM, has pioneered fruit fly control that uses a common insect-killing fungus, Metarhizium (Met) 69, that occurs naturally in the soil. Real IPM developed the system with funding from USAID and the Rockefeller Foundation.

Real IPM equips farmers with the powdered substance, which is used in traps. Flies that enter the traps are contaminated and exit the trap. They are able to contaminate other flies by grooming or mating before they die.

The system requires at least 20 traps per hectare. The fungus, which does not leave a residue because it is naturally occurring, can also be sprayed onto trees to infect larger adults or onto the soil to kill pupae.

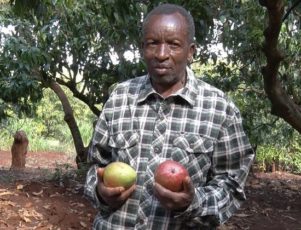

One farmer, Henry Ngari, told Reuters he is now able to sell 90 to 95 percent of his crop. “That’s a big improvement for farmers. We were losing around half of the crop because it was infected by fruit fly,” Ngari said.

Costs reduced

The system is initially more costly than chemical pesticides. But the traps only have to bought once, compared to many applications of pesticides. The system also greatly reduces manpower necessary to control fruit flies.

Ngari said he used to employ six men per day to spray chemicals. “Now it’s just one person to put a trap in place. That could be me or my wife,” Ngari said.

According to Sunday Ekesi, head of plant health at Kenya’s International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE), the use of bio pesticides is on the rise in Kenya. Companies including Dudutech, Kenya Biologics and Farmtrack Consulting also offer environmentally friendly tools to fight pests and plant diseases.

Growth in exports forecast

Experts believe bio pesticides will help Kenya’s growers further boost production and expand their export markets from the Middle East to Europe.

The United Arab Emirates imports more than 55 percent of the African nation’s mangos followed by Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Qatar.

Jonathan Bamber, whose Burton and Bamber buys from around 100 small farmers and produces dried mangos, said Kenya could become one of the world’s top producers. “It could be a huge revenue stream for small-scale farmers, if we can develop the market and demand, as well as the quality on the supply side,” Bamber said.